One of the most important motifs which recurs throughout The Great Gatsby is the motif of houses. The ways in which various characters relate to their houses reveals an extraordinary amount about their personalities, values, hopes, and dreams.

Almost every chapter in The Great Gatsby features a scene in which one of the main characters takes another character on a tour of his house. Why does the novel feature so many house tours? What does each house reveal about its owner? And what does each house tour reveal about its tour guide?

In this blog post, I’ll discuss how F. Scott Fitzgerald illuminates the personalities of various characters by describing how they present their houses to others. If you’re a teacher who’d like to explore the motif of houses with your students, then you’ll definitely want to check out this Complete Teaching Unit on The Great Gatsby.

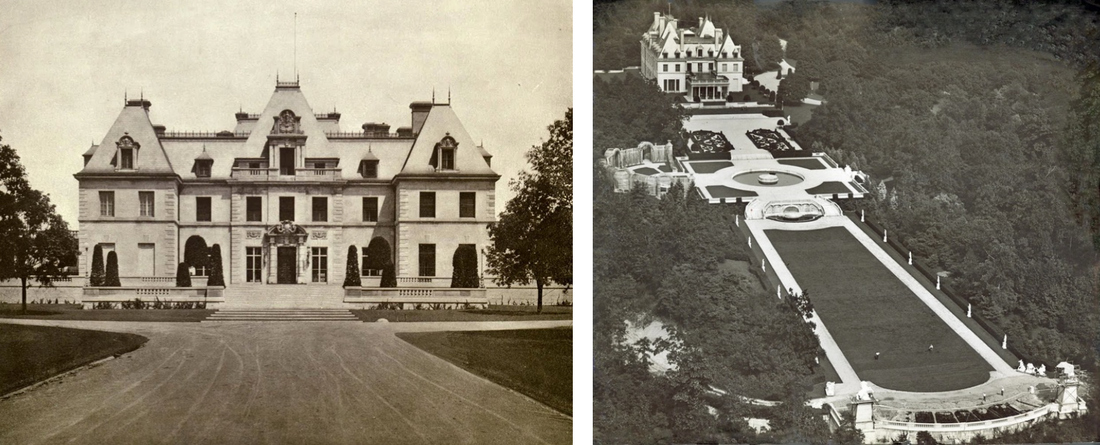

Chapter 1: Tom Buchanan's House Tour

When Nick Carraway travels to East Egg to visit his cousin, Daisy Buchanan, he is given a tour of the Buchanans’ house by Tom Buchanan. How does Tom conduct this house tour? What do Tom’s words about his house — or his treatment of his guest — reveal about his personality?

Standing on his front porch, Tom greets Nick with the assertion, “I’ve got a nice place here” (7). These are the first words that Tom speaks in the novel. Does his statement strike you as odd? The assertion that someone has “a nice place” should be made by a guest rather than by the host. The fact that Tom presumes the right to speak these words on behalf of his guest amounts to our first clue that he possesses a domineering and dictatorial personality.

The way in which Tom escorts Nick around his house similarly reveals that he possesses an imperious or domineering personality. Tom is a forceful tour guide who continually repositions Nick so that he’ll see exactly what Tom wants him to see. For example, Nick observes that Tom “turn[ed] me around by one arm” so that Nick could take in the vast expanse of the Buchanans’ yard (7). Nick proceeds to report that Tom “turned me around again,” abruptly announcing, “‘We’ll go inside’” (7).

Here, Tom’s use of the first-person plural pronoun “we” reflects that he presumes to speak and make decisions on behalf of his guest. Parodying Tom’s imperious tone, Nick mimics, “‘Now, don’t think my opinion on these matters is final,’ he seemed to say, ‘just because I’m stronger and more of a man than you are’” (7). Nick’s point is that Tom speaks with absolute finality, in a peremptory manner, brooking no dissent.

After they go back inside, Nick will dramatize the force with which Tom moves him from room to room by invoking the metaphor of a checkers game: “Tom Buchanan compelled me from the room as though he were moving a checker to another square” (11).

Tom’s body is so muscular and forceful that it seems to be endowed with its own agency, asserting itself in a manner that Tom seems unable to control. Nick hints at this dimension of Tom’s body when he describes how Tom’s muscles seem on the verge of bursting out of his feminine clothing: “Not even the effeminate swank of his riding clothes could hide the enormous power of that body — he seemed to fill those glistening boots until he strained the top lacing, and you could see a great pack of muscle shifting when his shoulder moved under his thin coat. It was a body capable of enormous leverage — a cruel body” (7).

Of course, the most important example of how Tom’s body seems to be endowed with a violent agency can be seen when he injures his wife. For Tom’s physical strength causes him to bruise and perhaps dislocate Daisy’s little finger, leaving the knuckle “black and blue” (12). Daisy asserts, “You did it, Tom. […] I know you didn’t mean to, but you did do it. That’s what I get for marrying a brute of a man, a great, big, hulking physical specimen of a ——” (12).

In all of these ways, Tom Buchanan gets depicted as an embodiment of a certain type of toxic masculinity. He presumes a right to take up space, to dictate the movements of other people, to steer conversations toward topics that he feels most comfortable with, and to interrupt or even injure the female characters who hazard to speak their minds or share dissenting opinions.

Chapter 5: Jay Gatsby's House Tour

In Chapter 5, Jay Gatsby takes Daisy on a tour of his house in West Egg. How are these two house tours — and the tour guides — similar? How are they different?

When Tom Buchanan gave Nick a tour of his house in East Egg, he began the tour with the brash assertion, “I’ve got a nice place here” (7). When Jay Gatsby gives a tour of his house, he begins the tour by asking, “My house looks well, doesn’t it?” (89). Fitzgerald endows these two comments with similarities and differences. While it is a little odd that both men compliment their own houses, Gatsby’s comment is at least phrased as a question, giving his interlocutor the freedom to agree or disagree.

A few minutes later, when Daisy emerges and asks whether Gatsby lives in “that huge place there,” Gatsby responds with another question: “Do you like it?” (90). What matters to Gatsby is not his own evaluation of the house but rather Daisy’s evaluation of it. When Gatsby is taking Daisy on a tour of his house, Nick observes that he “hadn’t once ceased looking at Daisy, and I think he revalued everything in his house according to the measure of response it drew from her well-loved eyes” (91).

While Jay Gatsby does not use physical force to conduct the tour of his house, he does seem to have staged and scripted the tour in advance. For example, Gatsby does not take the “short cut” to his house but escorts Daisy out to the road so that she can approach the house from the front and walk up the “marble steps” (90). So Gatsby is clearly hopeful that his guest will be impressed by what she sees, even if he doesn’t speak for her or compel any particular response.

The narrator’s description of the rooms in Gatsby’s house makes it sound as if the house is a museum designed precisely for the purpose of giving tours to visitors. Thus, Nick feels the ghostly presence of “guests” lurking in every room: “And inside, as we wandered through Maria Antoinette music-rooms and Restoration salons, I felt that there were guests concealed behind every couch and table, under orders to be breathlessly silent until we had passed through” (91). The house is less a residence intended to be lived in than a venue intended to welcome and entertain visitors. Gatsby’s bedroom may be the “simplest room of all” because it’s the only room not intended for public consumption (91).

Of course, Gatsby’s house tour culminates with the scene in which he shows Daisy his shirts. When Gatsby opens his cabinets, how does the narrator describe how his shirts are organized? How does Gatsby’s treatment of his shirts compare with the ways in which other characters use their clothing? Why might the sight of Gatsby’s shirts cause Daisy to “cry stormily” (92)?

The astonishingly poetic paragraphs about Gatsby’s shirts merit being read aloud and then discussed at length! When Gatsby opens his wardrobe, Nick describes Gatsby’s shirts as being “piled like bricks in stacks a dozen high” (92). By using a simile that compares the shirts to “stacks” of “bricks,” Fitzgerald implies that Gatsby’s shirts amount to their own carefully constructed house. The stacked shirts could be interpreted as a kind of house-within-a-house that functions like the play-within-a-play in William Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

But what’s most significant about this scene is that Gatsby is willing to take apart the brickwork of his shirts, to disassemble the elaborate edifice that he has worked for so long to build up, to let the house fall to pieces now that Daisy is with him. Gatsby’s house tour culminates with a pivotal moment in which he begins to toss his carefully stacked shirts onto a table so that they blend into a “soft rich heap” of “many-colored disarray” (92).

Why is it significant that Gatsby allows the brick-like shirts to collapse into a “soft rich heap”? Why is it significant that he allows the well-ordered “stacks” to collapse into a “many-colored disarray”?

In these evocative phrases, Fitzgerald uses a shift in sensory imagery — from hard to soft, from order to disarray — in order to track Gatsby’s willingness to relinquish his material possessions and external facade in favor of an emotional connection with Daisy. The material objects that had served to reflect their owner’s social status break down into their concrete sensory qualities.

Put another way, the signs of Gatsby’s materialism dissolve into their raw materials and their pure sensory materiality: beautiful colors, patterns, and textures. As Daisy presses her face into the soft textures of the shirts, she begins to “cry stormily,” exclaiming, “They’re such beautiful shirts. [...] It makes me sad because I’ve never seen such — such beautiful shirts before” (92).

Fitzgerald also establishes a contrast between the elegant whiteness of Daisy’s clothing and the colorful variety of Gatsby’s clothing. Daisy is named after a white flower, wears elegant “white dresses,” drives a “white roadster,” and makes sarcastic reference to her “white girlhood” (12, 74, 19). By contrast, Gatsby’s shirts come in a wide variety of patterns and colors: “shirts with stripes and scrolls and plaids in coral and apple-green and lavender and faint orange, with monograms of Indian blue” (92). The shirts come in a variety of sensuous textures that include “sheer linen and thick silk and fine flannel” (92).

Like his wardrobe, Gatsby’s house and grounds — together with his parties — are saturated with sensory stimuli ranging from colorful sights to fragrant smells and flavorful tastes. When Gatsby is escorting his guests through the grounds of his house, Daisy and Nick “admired the gardens, the sparkling odor of jonquils and the frothy odor of hawthorn and plum blossoms and the pale gold odor of kiss-me-at-the-gate” (90). Throughout these descriptive passages, Fitzgerald uses poetic diction and polysyndeton to emphasize the sensory plenitude and endless diversity and of Gatsby’s world.

In sum, Fitzgerald uses this scene to reveal a different side of Jay Gatsby, suggesting that what he values is not material wealth for its own sake but rather spiritual virtues such as aesthetic beauty and romantic love. Gatsby’s elaborate charade falls apart like a house of cards; and what's underneath is soft, tender, and loving.

Would it be a stretch to suggest that, when Gatsby tosses his shirts onto the table, he is metaphorically taking off his clothes? He is certainly relinquishing his ego armor, making himself vulnerable by letting his raw emotions show in all their exuberance. And this expression of authentic emotion causes Daisy to respond with a similar outpouring of emotion.

Toward the end of the house tour, the conversation between Gatsby and Daisy gets interrupted by the ringing of a telephone. When Gatsby answers the phone, he exclaims, “Well, I can’t talk now…. I can’t talk now, old sport.… I said a small town.…” (93). Who is calling for Gatsby? What is the significance of this phone call? Why might Fitzgerald have included this call in the novel?

In almost every chapter of Fitzgerald’s novel, the romance plot is haunted by the corruption plot. In Chapter 5, Gatsby’s reunion gets interrupted by a telephone call from a person who is probably involved in organized crime. In Chapter 4, Jordan Baker’s story about the early romance between Gatsby and Daisy in Louisville was preceded by a section in which Gatsby got associated with the crime boss, Meyer Wolfsheim.

Why is the romance plot constantly shadowed by the corruption plot? Gatsby’s efforts to reunite with Daisy have been enabled by his involvement in organized crime. If Gatsby succeeds in wooing Daisy, will he then be able to extricate himself from the world of organized crime? Or will that world prove to be inescapable? In books and movies that focus on mafia gangsters, characters who become involved in the world of organized crime inevitably find it hard to escape with their hands clean....

Chapter 9: Henry Gatz Visits Gatsby's House

While standing in the hallway of his son’s house, Henry Gatz reaches into his wallet and pulls out a photograph of that very same house. The photograph is described as being “cracked in the corners and dirty with many hands” (172). Nick reflects that Mr. Gatz “had shown it so often that I think it was more real to him now than the house itself” (172). Is it odd that Mr. Gatz seems more absorbed by a photo of Gatsby’s house than by the house itself? Do Mr. Gatz’s actions reveal any resemblances between father and son?

I love this textual detail for so many reasons! First, Jay Gatsby has sent his father a kind of portrait photograph not of himself but rather of his house. This says so much about Gatsby’s self-perception. Second, Henry Gatz is standing inside the enormous house itself; and yet he is absorbed by the small photograph of the house!

He’s even fixated on the details in the photograph rather than the architectural details that surround him: “He pointed out every detail to me eagerly. ‘Look there!’ and then sought admiration from my eyes” (172). The fact that Henry Gatz looks for the “admiration” in Nick’s “eyes” conveys how things seem to become more valuable when they’re admired or sought out by many others. And Henry Gatz has clearly made a ritual out of showing off this photograph to other people; for the father’s pride in his son’s accomplishments is reflected in the fact that the photograph has become “dirty with many hands.”

For all their differences, then, Henry Gatz and Jay Gatsby are similar in that both characters become more enchanted by an image of a desired object than by the object itself. As we have seen, Gatsby comes to love an “idea” of Daisy as much as he loves the real person. He remains in love with the memory of Daisy as she existed in the past rather than the reality of who Daisy is in the present; and during the five years when they are apart, Gatsby builds up and embellishes his dream of Daisy until the real but flawed person can hardly compete. Nick concludes, “There must have been moments even that afternoon when Daisy tumbled short of his dreams — not through her own fault, but because of the colossal vitality of his illusion” (95).

This scene in which Henry Gatz can’t keep his eyes off a photograph of the house even while standing inside the house parallels a previous scene in which Gatsby couldn’t keep his eyes off the green light even while standing next to Daisy. After giving Daisy a tour of his house, Gatsby gazes across the Long Island Sound and says, “You always have a green light that burns all night at the end of your dock” (92). At this point, Daisy links arms with Gatsby; but he seems oblivious to her physical proximity because his attention is still fixed on the green light that represents his distant and idealized image of Daisy: “Daisy put her arm through his abruptly, but he seemed absorbed in what he had just said” (93).

Finally, while Gatsby has suppressed details about his family history when building his new life, the fact that Henry Gatz arrives with a photo of Gatsby’s house reveals that Gatsby has not severed all communication with his parents. Mr. Gatz reveals that Gatsby has visited his father in the Midwest and has even purchased a new house for his parents: “He come out to see me two years ago and bought me the house I live in now” (172). Needless to say, these textual details help to make Gatsby’s character more sympathetic. But it’s no accident that Gatsby has never spoken with anyone in New York about this second house that he’s bought.…

Want to Learn More?

If you’re a teacher or student who would like to explore the motif of houses in even greater depth— along with many other motifs — then you’ll definitely want to check out this Complete Teaching Unit on The Great Gatsby.

The 200-page resource packet is filled with discussion questions, vocabulary lists, reading quizzes, and writing tasks for every chapter of The Great Gatsby. Best of all, it features detailed answer keys informed by the most insightful academic scholarship on The Great Gatsby!

Save yourself hundreds of hours of prep time while motivating your students to be highly engaged! Don't forget to check out this Complete Teaching Unit on The Great Gatsby!!